By Janet Wolfson, PT, CWS, CLT-LANA

After landing my dream job as the wound care coordinator at an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), I found myself trying to determine how much healing could be achieved for our more challenging patients, given the constraints of reimbursement and what can be done in the typical 10 to 14 days of a patient stay.

Here’s an example of how I worked with our team to help one of these challenging patients.

Mr. B arrives

Mr. B was a Medicare patient admitted to the IRF after months of hospitalization for bilateral diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) on the plantar surfaces, diabetic neuropathy, bilateral lower extremity lymphedema elephantiasis, gangrene, bilateral fungal infection with thick fungal scale and callus from the toes to the upper calves, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), heart failure (HF), coronary artery disease, a stage IV pressure ulcer in the sacral area, acquired polymyopathy, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

If I had high-tech ultrasonic debriders, skin substitutes, growth factors, and 4 hours to dedicate to Mr. B each day, I knew I could have a significant impact. But a reality check focused me to think about what I could do in a few short weeks to accelerate the healing journey of this man: What were realistic short-term goals?

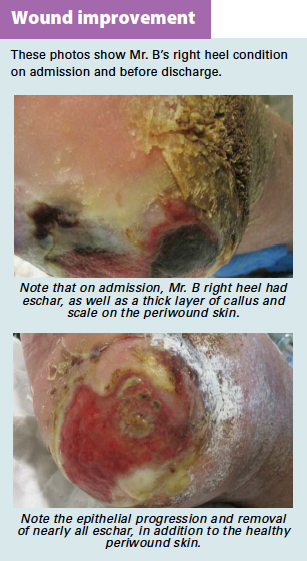

Closure of his complicated wounds couldn’t be the goal, so I decided that I could reduce or remove necrotic tissue or biofilm from his DFUs; disinfect and bluntly remove the thick scale and callus on his lower legs and feet that was composed of fungus, dead tissue, and other debris; prevent worsening of the pressure ulcer; and increase granulation tissue and epithelialization in his wounds.

Edema was present bilaterally, but with HF, MRSA, ESRD, and only 3 weeks before Mr. B’s expected discharge, I knew I wasn’t going to be able to significantly address this. After reflecting on previous successful regimens used for similar patients and consulting colleagues who are experts in wound care and lymphedema, I embarked on a plan that included patient education on lymphedema, pressure relief, diabetic foot care, and skin care. I optimized Mr. B’s treatment by reviewing wound products available in our facility and adding more as needed, promoting good communication among staff stakeholders, and reaching out to the community for discharge planning.

Stakeholders step up

I knew that I alone couldn’t provide everything this patient needed. I identified and sought to involve many members of our facility’s wound team to maximize the benefit of Mr. B’s rehab stay. Each of us had an important contribution to make.

As a certified wound and lymphedema specialist, I was the cornerstone to optimize Mr. B’s wound and lymphedema care. My credentials and experience enabled me to determine the cause of his pressure ulcer and DFUs, stage them, and know the phase of wound healing for each. I removed necrotic and nonviable tissue through a series of sharp debridement of his DFUs and blunt debridement via tongue blade on the leg scales. Mr. B’s wounds progressed from the inflammatory towards the proliferative phase, which increased the healing rate.

Our physicians and pharmacists addressed Mr. B’s MRSA with I.V. antibiotics. The nephrologist and internist advised me that because of Mr. B’s ESRD and HF, he wasn’t a candidate for leg compression. The dietitian maximized Mr. B’s nutritional wound support within his disease-related dietary restrictions. The nursing staff tracked his blood glucose level and delivered medications to support wound healing; they also provided dressing changes.

All staff, from certified nursing assistants to therapists, promoted pressure relief and provided direct hygiene and skin care while teaching Mr. B so he could eventually take over his own care. The dialysis nurse positioned Mr. B on a low-air-loss mattress for pressure relief during dialysis.

The RN admission assessment had provided me with Braden scores and a body mass index so that I could order the proper durable medical equipment (DME) needed to relieve Mr. B’s pressure areas. Our purchasing clerk provided the support surfaces and the appropriate bandage supplies. Timely ordering and delivery of supplies that were being used faster than normal ensured Mr. B received the treatment he needed. Access to the manufacturer’s catalog allowed me to request wound cleansers, antimicrobial dressings, and high-absorbency foams to enhance Mr. B’s treatment and decrease frequency of changes. Off-loading shoes allowed Mr. B. to improve his mobility while protecting his plantar ulcers.

Ready for discharge

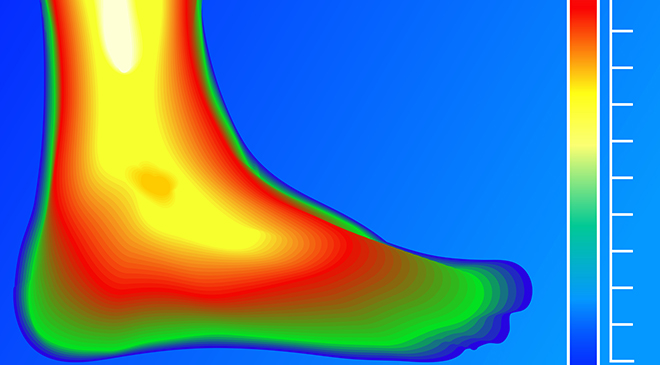

After a bit over 3 weeks, Mr. B was ready for discharge. The short-term goals of removing necrotic tissue, reducing bioburden, and increasing granulation had been met. (See Wound improvement.) Because complicated wounds can take much longer to heal than a short inpatient stay allows, knowledge of local resources to keep Mr. B on a healing continuum was vital.

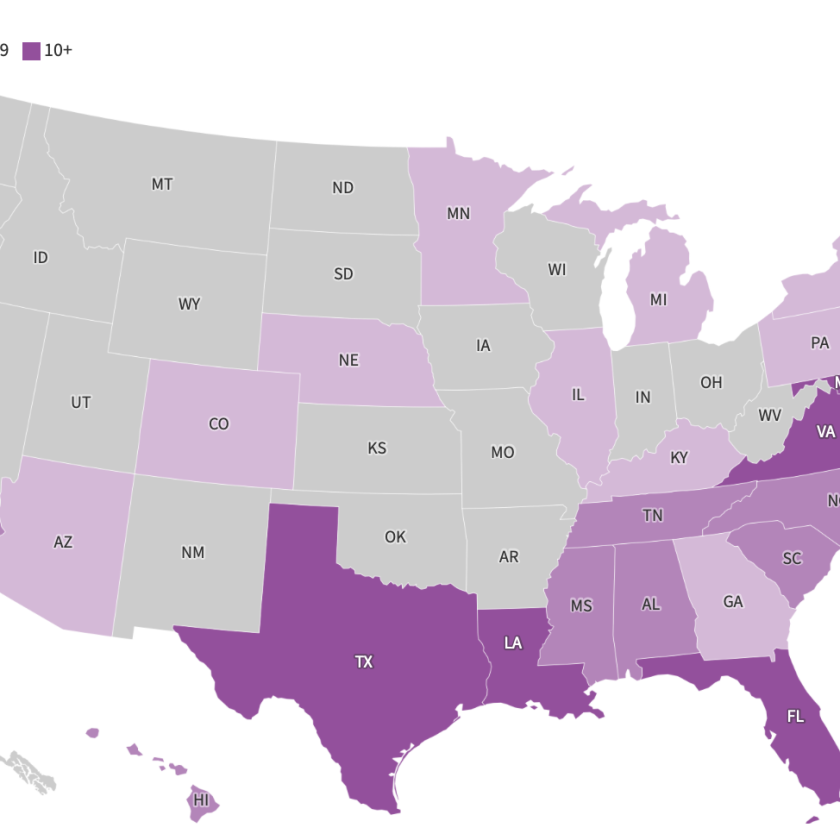

Mr. B left our IRF knowing his expectations for wound healing and ongoing care. Printed instructions and predischarge teaching were part of this. Communicating his needs to case managers helped ensure he was put in touch with community resources. Community partners included family members, nongovernment organizations for DME funding, diabetic educators, podiatrists, wound centers, hyperbaric technicians, lymphedema therapists, infectious disease physicians, home care agencies, and support groups.

Making a difference

Because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services constricts reimbursement and incentivizes quality care, facilities maximizing patient benefits while being cost effective will have the edge in the marketplace, particularly in the case of patients like Mr. B. Now is the time for each IRF facility to assess its wound care product inventory, reflect on the facility’s team for provision of wound care, and expand its network in the community. Tracking readmissions within 30 days back to the acute referral source enables a facility to monitor progress. These actions can help ensure the facility can maximize patient outcomes and be a leader in the community.

Janet Wolfson is a wound care coordinator at HealthSouth Ocala in Florida.

Selected references

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Bundled payments for care improvement (BPCI) initiative. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/

Scarborough P. Understanding your wound care team: defining unidisciplinary, multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary team models. Wound Source. 2013.

White-Chu EF, Reddy M. Wound care in short-term rehabilitation facilities and long-term care: special needs for a special population. Skinmed. 2012 Mar-Apr; 10(2):75-81.

DISCLAIMER: All clinical recommendations are intended to assist with determining the appropriate wound therapy for the patient. Responsibility for final decisions and actions related to care of specific patients shall remain the obligation of the institution, its staff, and the patients’ attending physicians. Nothing in this information shall be deemed to constitute the providing of medical care or the diagnosis of any medical condition. Individuals should contact their healthcare providers for medical-related information.